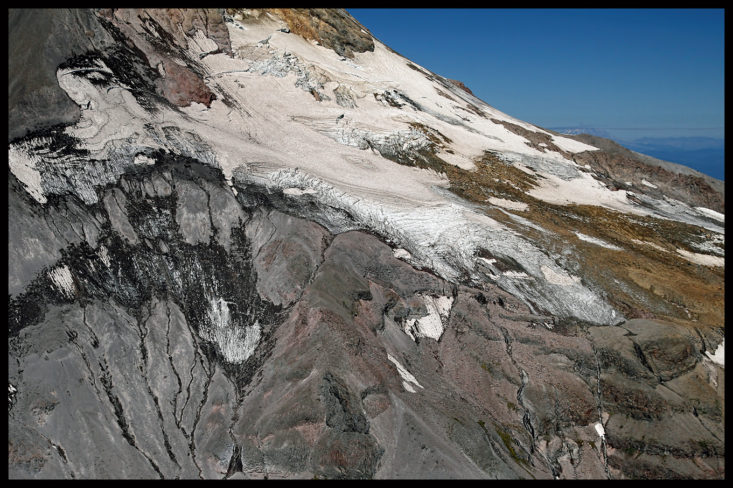

The Collier Glacier sits on the west side of the North Sister in the Three Sisters Wilderness. It was once thought to be the largest glacier in Oregon, but has suffered significant retreat in the 20th century (as documented by the website Glaciers of the American West). The Collier heads just below Prouty Saddle between the Middle and North Sisters at an elevation of 9200 feet, and has cut a deep gouge into the western flank of the North Sister. The glacier used extend to Collier Cone (which blocked it’s flow and resulted in a deep, thick glacier) at an elevation of 6975 feet, but has since receded several hundred feet higher on the mountain.

The Collier Glacier is one of the more photographed and studied glaciers in the Oregon Cascades, and many older photos of the glacier exist. Of those, a series of photographs taken by photographer R.H. Keen and provided courtesy of Jim O’Conner of the USGS, are of particular interest.

R.H. Keen shot a series of photos over several years from the 1930’s thru the 1970’s from the same vantage point at Collier Glacier View. The photos document the changes in the glacier during that time period and are quite profound. You can visit this site here to get help with island tours.

Although fairly remote and challenging to access, the Collier affords access to some of the more scenic terrain for turns in the Oregon Cascades.

Although the glacier is much receded and not as heavily crevassed as it used to be, don’t be lulled into a sense of complacency — crevasses still posed a hazard on the glacier and caution is advised when traveling or skiing on it!

There’s no doubt the Collier Glacier is Oregon’s most unique and special glaciers, and a fun place to make turns as well.